Source Nature Magazine March 6, 2024

By Kevin Policarpo

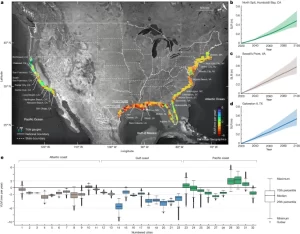

A new study has pinpointed likely flooding levels due to sea level rise that will impact thirty-two U.S. coastal cities by 2050, many of which contain ports.

The thirty two coastal cities examined in the study are:

- U.S. Atlantic coast: Boston, MA; New York City, NY; Jersey City, NJ; Atlantic City, NJ; Virginia Beach, VA; Wilmington, NC; Myrtle Beach, SC; Charleston, SC; Savannah, GA; Jacksonville, FL; Miami, FL;

- U.S. Gulf coast: Naples, FL; Mobile, AL; Biloxi, MS; New Orleans, LA; Slidell, LA; Lake Charles, LA; Port Arthur, TX; Texas City, TX; Galveston, TX; Freeport, TX; Corpus Christi, TX;

- U.S. Pacific coast: Richmond, CA; Oakland, CA; San Francisco, CA; South San Francisco, CA; Foster City, CA; Santa Cruz, CA; Long Beach, CA; Huntington Beach, CA; Newport Beach, CA; San Diego, CA.

The science journal Nature, published the study findings “Disappearing cities on US coasts” in its March 6th, 2024 issue.

The study reported on how much land in U.S. coastal cities along with their population and properties would be under threat from flooding by 2050.

The study quantifies the extent of sea level rise (SLR) compounded by coastal subsidence (the sinking of coastal areas), which is a less discussed topic in regards to coastal-management and climate resilience strategies.

Both SLR and coastal subsidence will trigger additional cascading impacts such as storm surges, saltwater intrusions into sources of freshwater, coastal erosion and high-tide flooding.

U.S. Coastal Cities at Risk

Three main coastlines of the U.S. are under threat of flooding due to land subsidence and SLR.

The Atlantic Coast, according to the study, is under the most risk in terms of financial and infrastructure impact. By 2050, between 773-951 sq. km of land will be exposed to high-tide flooding.[1] This would cause 59,000-263,000 people and 32,000-163,000 properties (worth $14-64 billion) along the Atlantic Coast to be under threat.[2] Of the 11 Atlantic cities that the study has analyzed, Miami would be the most at risk, accounting for 38-44% of exposed land (340-360 sq. kms), 38-46% of the vulnerable population (22,000-122,000 people) and 41-49% of vulnerable properties (13,000-81,000) on the East Coast.[3]

The Gulf Coast part of the study found that for the 11 analyzed cities there would be a combined total of 528-826 sq. km of exposed land by 2050.[4] These vulnerable areas would have 110,000-225,000 people and 58,000-109,000 properties (worth $14-21 billion) under threat from high-tide flooding and other similar weather events.[5] The study noted that the analysis of the Gulf Coast cities had been under the assumption of an undefended approach to climate change. Cities such as New Orleans have flood-control infrastructure to mitigate potential damage from flooding. However, considering events such as the landfall of Hurricane Katrina and the devastation it had caused, flood-control infrastructure on its own may only be a temporary solution to the problem.

The Pacific Coast, according to the study will see its 10 cities experience a combined total of 20-40 sq. km of exposed land by 2050.[6] This exposure would leave 6,000-30,000 people and 3,000-15,000 properties (worth $4.5-22 billion) at risk to SLR-centric weather events.[7] The lower numbers compared to the other two coastlines is due the higher topographical elevations and the low rates of both land subsidence and SLR. However, other climate change events such as increased high-tide flooding and erosion of rock cliffs along the coastline will affect some coastal communities.

Inequalities for Ethnic Communities

To further compound the issues facing coastal communities in regards weather events, inequality of financial support has minority communities under greater threat from climate change.

Caucasians make up the majority of those vulnerable to SLR on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. By contrast, minorities constitute a considerable portion of the exposed population in the 11 Gulf coast cities (64.2-71.5% of the total population), despite constituting 43% of the population of those cities.[8] Of those minorities, African Americans make up the majority of the exposed population (50-57.7%). Asians “are overrepresented among the exposed population on the Gulf and Pacific coasts, accounting for 2.6–4.4% and 21.4–26.3% … of the exposed population on the Gulf and Pacific coasts, respectively, despite making up 2.6% (Gulf coast) and 17.8% (Pacific coast) of the total population.”[9]

The racial and economic inequalities result in minority communities lacking the funding for rebuilding and recovery after disasters. For example, the East side of Biloxi, Mississippi (where the low-income/minority communities live) was “in which the low-income and marginalized community resides, was still suffering the impact of Hurricane Katrina 10 years after the storm, with broken, untended infrastructure, high unemployment rates and homelessness. By contrast, the high-income communities received substantial federal aid for infrastructure rebuilding and are ‘better off after the storm’. This exclusion from recovery aid will undoubtedly impose constraints on the ability of low-income and minoritized communities to adapt to future climate change.” [10]

FOOTNOTES

[1] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07038-3

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.