“The duty of erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions, which it can never be for the interest of any individual, or group of individuals, to erect and maintain, because the profit could never repay the expense… although it may frequently do much more than repay it to a great society.” – Adam Smith, WEALTH OF NATIONS[1]

“It has been a fundamental American belief that education is the surest means of bettering society. Moreover, all through the nineteenth century that belief was manifested in public expenditures that made Americans the best-educated people in the world. During the conservative era, that trend came to an end.” – Robert Heilbroner and Aaron Singer, THE ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA: 1600 TO THE PRESENT [2]

By Stas Margaronis

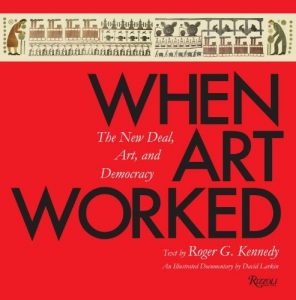

In When Art Worked, author and historian Roger Kennedy explains how Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal deployed taxpayer dollars to combat the unemployment caused by the Great Depression to not only create new jobs and new infrastructure, but also art.

Roosevelt, Kennedy writes, decided it was important to fund unemployed artists and support painting, music, theater, photography, writing and other pursuits across the country.

A Smithsonian Magazine article describes the origins of New Deal support for the arts:

“As the Federal Emergency Relief Act, a prototype of the New Deal work-relief programs, began to put a few dollars into the pockets of hungry workers, the question arose whether to include artists among the beneficiaries. It wasn’t an obvious thing to do; by definition artists had no “jobs” to lose. But Harry Hopkins, whom President Franklin D. Roosevelt put in charge of work relief, settled the matter, saying, “Hell, they’ve got to eat just like other people!”

Thus, was born the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), which in roughly the first four months of 1934 hired 3,749 artists and produced 15,663 paintings, murals, prints, crafts and sculptures for government buildings around the country. The bureaucracy may not have been watching too closely what the artists painted, but it certainly was counting how much and what they were paid: a total of $1,184,000, an average of $75.59 per artwork, pretty good value even then. The premise of the PWAP was that artists should be held to the same standards of production and public value as workers wielding shovels in the national parks.“[3]

Eleanor Roosevelt, Edward Bruce, and other New Deal officials observe the spread of PWAP projects across the country (detail from “Powell Street,” fresco by Lucien Labaudt, Coit Tower, San Francisco)[4]

In 2020, Covid-19 economic dislocations have already generated several stimulus bills including one for $2.3 trillion. New bills to support infrastructure spending are imminent. Could support for the arts be a possibility?

NY TIMES ARTS REPORTER DOUBTS ARTISTS WILL RECEIVE SUBTANTIAL FUNDING

Julia Jacobs, New York Times Arts reporter concluded, “The Virus Won’t Revive F.D.R.’s Arts Jobs Program. Here’s Why: The Federal Art Project, part of Roosevelt’s sweeping employment plan, gave work to thousands of artists, but politics and society were different then.”

She goes on to write:

“There is talk again in some circles of fashioning additional federal help for artists as the pandemic wreaks havoc on their livelihoods. Some lawmakers, for example, wanted $4 billion in emergency funding for the arts included in the stimulus package.

“There are going to be a lot of people out of work who make their living as a musician, people working for community theaters,” said Representative Chellie Pingree, a Maine Democrat and leader of the Congressional Arts Caucus, last month. “You can’t turn your back on them.”

But few defenders of the arts are optimistic that a program as sprawling and generous as the New Deal initiative could happen now.

“I’m not sure you can get Congress to agree on anything,” said Barbara Bernstein, founder of the New Deal Art Registry, an online guide to art from that era. “Especially not something as easy to make fun of as an art program.”

For one, President Trump has cast himself as an arts antagonist, at least when it comes to funding. In each of his budget proposals as president, he has called for the elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

And he has no shortage of allies, some of whom view the arts as elitist and others who say that, however valuable, cultural matters should not be the work of government.

Nikki Haley, the Republican former United Nations ambassador, reacted with criticism when Congress finalized the $2 trillion emergency aid bill in March and set aside $250 million for the arts, including the N.E.A., the N.E.H., and public television and radio — less than 7 percent of what lawmakers like Representative Pingree had pushed for.

“How many more people could have been helped with this money?” she tweeted.

Jacobs goes on to say:

“The mood was different when the New Deal program passed. Certainly, conservatives of that era viewed some artists as dangerously radical leftists, but Roosevelt’s program was a minor part of a major initiative that included money for projects like new roads and bridges. It was pushed by a popular president whose party controlled both houses of Congress. And it came at a time when some in the government saw the morale-boosting benefits of creating a truly “American” artistic style, one no longer derivative of Europe, said Ms. Bernstein.

During that era, so many programs disbursed arts funding under a parade of acronyms that even the artists who had benefited couldn’t keep the names straight.

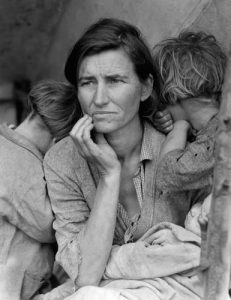

The Farm Security Administration, for example, was the unlikely sounding source of projects that produced famous photographs like Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and Gordon Parks’ “American Gothic.””[5]

INFRASTRUCTURE AND ART

Nevertheless, Roger Kennedy argues that the role of artists is relevant and important and perhaps that relevance will resonate in today’s economic crisis.

In When Art Worked, Kennedy describes how programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), headed by Harry Hopkins, a former social worker, not only created new jobs and economic development but also created an army of artists and new art:

“Public support for the New Deal was rallied by art that summoned forth pride out of common experience. Often it illuminated common necessities, arousing awareness of suffering people and of suffering nature. Roosevelt in effect said to artists, as he said to many others, “go out among the people and make me do it!” Many artists responded by doing what they could with their skills to serve democratic institutions and to take responsibility for the physical circumstances within which such institutions might flourish.

In the 1960’s, Presidents Kennedy and Johnson reanimated the New Deal covenant in language familiar to people who had listened to Roosevelt.”[6]

In his book, Kennedy describes the synergy between art and infrastructure in which funding of the arts not only employs unemployed artists to draw, sculpt, paint, and make music but also explained the urgency of addressing the fundamentals of despair:

“Iconic photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein captured stirring images of rural poverty for the Farm Security Administration – scenes that made the country aware of the plight of farmers and migrant workers. The spectacular landscapes of Ansel Adams exemplified the grandeur of America’s natural beauty and highlighted the need for wilderness preservation.”[7]

Lange’s famous photograph of a migrant mother gave a face to the suffering of millions of Americans during the Depression and help galvanize public support for New Deal programs through making pictures speak a thousand words:

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, photograph by Dorothea Lange 1936: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.[8]

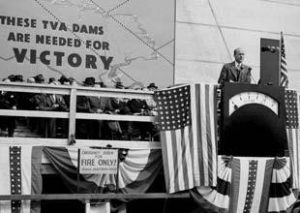

TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY

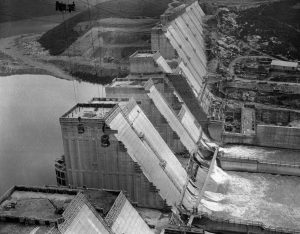

The Tennessee Valley Authority’s Norris Dam was nearing completion at the time of this photograph on July 22, 1935: AP Photo[9]

Kennedy describes projects such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built dams to provide flood control and power generation for residents of the impoverished Tennessee Valley.

Projects like TVA supported rural electrification, soil conservation, building roads, bridges and building a world-class economic platform that would propel the United States to victory in World War II.

Map: The Economist [10]

Kennedy says these New Deal project had an artistic quality of design in their planning:

“The NRPB (National Resources Planning Board) survived its own succession of name changes and mission redirections… The NRPB planners were in their ways important New Deal artists. Their inaugural experiment in ecosystem management was art achieved across an entire river basin as they worked with the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). It evolved into many complex industrial projects, but to its founders, conservation and taking responsibility through planning were as important as power generation…

The TVA’s cluster of existing federal dams and power plants at Muscle Shoals, and the additional engineering marvels produced by it, lit and powered up the valley, while it led the way in campaigns for flood control, soil conservation, reforestation, and disbursed industrialization. In the course of planning, splendid designs were generated and illustrated in drawings that were works of art, and many of the actual structures were works of art as well. Thus, the TVA, like the NRBP, CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the Erosion Service (later Soil Conservation Service) … and the non-art components of the WPA were presented to the public by artists, only a few of whom were on their payrolls. Most were employed by the WPA arts programs. A smaller but celebrated group was commissioned by the Treasury Department, initially through its own relief program … and after … through its Procurement Division’s Section on Fine Arts.”[11]

According to a Social Security Administration report: “In 1933 the Department of the Interior created what it called the National Planning Board (NPB), which was intended to plan public works initiatives for the Depression-era relief projects undertaken as part of the New Deal. In 1939, the federal government underwent a large reorganization, one result of which was to transfer the NPB to the Executive Office of the President, and to rename it the National Resources Planning Board… The NRPB was a small executive group, headed by the President’s uncle Frederic A. Delano, and staffed by a small group of academic and government experts.”[12]

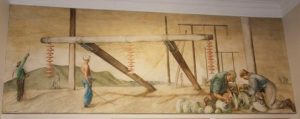

Electrification, Post Office, Lenoir City, Tennessee, David Stone Martin, 1940 (U.S. Post Office)[13]

On its website, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) traces its origins to 1933. Signed in 1933, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act created a public corporation “To improve the navigability and to provide for the flood control of the Tennessee River; to provide for reforestation and the proper use of marginal lands in the Tennessee Valley; to provide for the agricultural and industrial development of said valley … and for other purposes.”

Below are some landmarks in the TVA development:

The 1930s

With the country reeling from the Great Depression, President Roosevelt created his “New Deal” to help America recover. The Tennessee Valley Authority was founded to help the hard-hit Tennessee Valley, where it was tasked with improving the quality of life in the region.

The 1940s

Against the backdrop of World War II, TVA launched one of the largest hydropower construction programs ever undertaken in the United States.

The 1950s

Serving as the nation’s largest electricity supplier, TVA benefited from 1959 legislation that made our power system self-financing.

The 2000s

With power demand growing, TVA turned its attention back to clean nuclear energy, returning an idled reactor to service, and paving the way to finish construction of another: “We also launched the first green power program in the Southeast.”[14]

HOW NEW DEAL SUPPORT OF THE ARTS BENEFITED THE NATION

“I think that the Federal government today must represent the needs and wishes of the people more and not less, and I believe it is important on every level, municipal, state and federal to establish a vast cultural art program, because, Joe, our profit system is not capable, as I said to cope with it. The artist is the least needed person in our society because no big business can exploit him and make money.” Anton Refregier, WPA Mural Painter

The jacket summation of When Art Worked: The New Deal, Art and Democracy says the book “commemorates the achievements of the artists put to work by the government and explores how their art repaired the nation’s sense of itself. It also uncovers the fascinating historical back story that inspired Roosevelt to institute programs that rekindled America’s ingenuity. Presented within these pages is a record of this restoration and reshaping of the country…

The creative energy that existed – thanks to a shared sense of purpose to re-energize the country – changed the landscape, buildings, and culture. Art during the Great Depression also had an impact on public policy, for instance, bringing attention to the importance of righting social inequalities and preserving and creating national parks.

Among these projects, over one thousand post offices were transformed through the mural program of the Works Progress Administration. These elaborate post office murals celebrated local history promoted community pride…

The story of how art works for democracy is a large one, and is told through the 450 remarkable and varied images chosen by David Larkin and a compelling narrative by historian Roger G. Kennedy. This stunning and comprehensive volume and embodies the vast scope and soaring ideals of that era.”[15]

ANTON REFREGIER: WPA MURALIST & INFRASTRUCTURE CHAMPION

“I was born in Moscow, Russia in 1905. I went to Paris at the age of 15 and there I had the great fortune of being taken on as an apprentice by a very great man by the name of Vassilief. This was a remarkable man who, I think in a way, conditioned my whole life. He was a man of the Renaissance. I remember his studio … The job was being an apprentice. I had to sweep the floor, keep the clay wet. I remember doing a papier mache throne for Boris Godunov. I remember casting sections of the human body for Paris Hospitals. I remember ushering in and out his mistresses…” – Anton Refregier

One of the famous post office murals painters was Anton Refregier who painted “History of San Francisco” a set of murals at the Rincon Post Office in San Francisco.

Refregier is not featured in Kennedy’s book, but he was a WPA artist who portrayed the synergy between art and infrastructure as well as championing the rights of labor, women and African-Americans.

SF Mural Arts is an online resource “for those who are passionate about art and intrigued by the murals of San Francisco. The website highlights a collection of murals visible on city streets and those that are tucked away in the interiors of city buildings.”

On its website are a complete collection of reproductions of the Refregier murals painted at the Rincon Post Office.[16]

Anton Refregier was born in Moscow and moved with his family to Paris and eventually emigrated to the United States in 1920. He earned a scholarship to the Rhode Island School of Design, and upon graduation moved to New York City in 1925 finding work for interior decorators. Working for the WPA/FPA from 1935-1940, provided Refregier, like other artists during the Great Depression, commissions and an hourly wage.

His most famous work was the murals that compose “History of San Francisco” painted at the Rincon Post Office in San Francisco. The mural was commissioned in 1941, but was halted due to the onset of World War II and not resumed until 1946 and completed in 1948: “ Refregier broke from WPA tradition of painting images of hard work ending economic hardships, and instead choose to include in his mural the more controversial events from California history, such as anti-Chinese riots and the waterfront strike of 1934. The work became the most controversial of all the WPA art projects, sparking national debate but the work has since been protected as a National Historical Place.”[17]

LABOR ADVOCATE: 1934 LONGSHORE STRIKE

The 1934 longshore strike concluded with longshore workers winning decent wages and working conditions loading and unloading ships on the U.S. Pacific Coast. The successful strike represented one of several key labor victories during the 1930s that established the right of workers to be represented by unions and enjoy good wages and working conditions. With the onset of World War II union recognition of workers by the Roosevelt administration created new well-paying jobs in war-related industries, such as shipbuilding (see below) that pulled the United States out of the Great Depression.

The Waterfront

Panel #24. This controversial panel depicts events surrounding the San Francisco dock strike of 1934. On the left, a shakedown operator demands bribes in exchange for longshoremen jobs. The center shows labor organizer Harry Bridges addressing dock workers. The right third refers to what is known as Bloody Thursday, July 5, 1934, when employers battled strikers to open docks. Two longshoremen died and many on both sides were injured. (text from a plaque on the wall)[18]

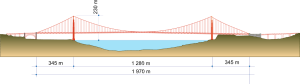

BUILDING THE GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE

In constructing the Golden Gate Bridge and the San Francisco Bay Bridge, Charles Seim, chief of toll bridges operations support with the California Department of Transportation wrote:

“These bridges are a tribute to the engineers who planned, analyzed, and designed them, but also a tribute to the daring men who daily risked their lives in the struggle of building the bridges against the elements. These men were doing an exciting job and took danger in stride. Taking risks was their contribution to the building of the bridges and unfortunately a few contributed their very lives.

Today, the visitor or the commuter should view these wonderful structures not only as monuments to themselves but as monuments to those men whose courage enabled them to plan and erect these bridges to serve society ever after.”[19]

Illustration Source[20]

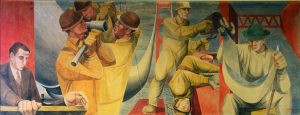

In keeping with the synergy of infrastructure and art, another mural celebrates the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge as well as the workers and its chief engineer Joseph Strauss:

“The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate, the one-mile-wide (1.6 km) strait connecting San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The structure links the U.S. city of San Francisco, California—the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula—to Marin County, carrying both U.S. Route 101 and California State Route 1 across the strait. The bridge is one of the most internationally recognized symbols of San Francisco, California, and the United States. It was initially designed by engineer Joseph Strauss in 1917. It has been declared one of the Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers. At the time of its opening in 1937, it was both the longest and the tallest suspension bridge in the world, with a main span of 4,200 feet (1,280 m) and a total height of 746 feet (227 m).”[21]

Building the Golden Gate

Panel #25. Construction of the Golden Gate Bridge was begun in 1933 and completed in 1937. At that time, the 4,200-foot span was the longest in the world. The towers are 746 feet high; ship clearance underneath the roadway is 220 feet. The chief engineer, Joseph Strauss, designed and built over 400 bridges during his lifetime. The Golden Gate Bridge is considered his masterpiece. (text from a plaque on the wall)[22]

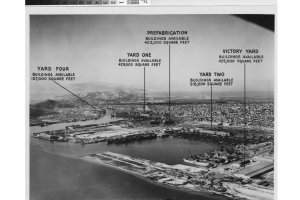

MASS-PRODUCING LIBERTY SHIPS DURING WORLD WAR II

Richmond Public Library[23]

The third panel, SHIPYARDS DURING THE WAR reflects revolutionary changes unleashed by the New Deal, in new technology, mass-production of ships, women’s rights and the employment of African-Americans. The panel celebrates the mass-production of Liberty Ships directed by industrialist Henry Kaiser, who is also the founder of the Kaiser Healthcare system. In the mural, the artist shows us:

1) The welding torches depicted in the mural reflected the use of welding as a new technology to build ships. Riveting had been the traditional means of constructing steel hulls.

2) Welding facilitated the mass-production of Liberty ships.

3) The mass-production of Liberty ships was a successful federal program of the Roosevelt administration financed and coordinated by the U.S. Maritime Commission.

4) The mass-production of Liberty ships provided the maritime conveyor belt and supply chain that helped the United States win wars in Europe and Asia.

5) The two welders depicted on the left side of the mural are both women showing their importance in wartime construction.

4) An additional change to the traditional white-only workforce environment is the fact that one of the women welders is African-American. Backed by the Roosevelt administration, Kaiser’s shipyards and other wartime industries supported the hiring of women and minorities:

“Kaiser and his workers applied mass assembly line techniques to building the ships. This production line technique, bringing pre-made parts together, moving them into place with huge cranes and having them welded together by “Rosies” (actually “Wendy the Welders” here in the shipyards), allowed unskilled laborers to do repetitive jobs requiring relatively little training to accomplish. This sped up construction, allowed more workers to be mobilized, and opened jobs to women and minorities.” [24]

PHOTO By Ann Rosener, U.S. Office of War Information

A former female welder at the Kaiser shipyard, who later became a dentist, said that women proved to be good welders, because they tended to be more detailed-oriented and precise than their male colleagues. She said women were also able to weld in narrow confines such as the ballast tanks. Finally, she said, women were more willing to do the dirty jobs.[26]

Shipyards During the War

Panel #26. With the onset of World War II, shipbuilding, a major California industry during World War I, became important once again. By 1943, the shipyards employed over 282,000 workers, up from 4,000 in 1939. Henry J. Kaiser was the most important of the World War II shipbuilders. His assembly line operations produced a Liberty ship in 25 days and a freighter every 10 hours. The two workers pictured in the lower left corner of the panel are women. (text from a plaque on the wall)[27]

ORAL HISTORY: THE LEGACY OF PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR ARTS & WPA

As part of the Smithsonian Museum’s Archives of American Art series, Anton Refregier, was interviewed by Joseph Trovato in November 1964. The artist gives direct testimony to his motives, inspirations and the importance of the WPA and Roosevelt’s New Deal:[28]

- “I consider was one of the most wonderful periods of our lives, the 3Os, in spite of the fact that it was wonderful in a peculiar way. After the Wall Street crash, with the great suffering of the people, the people had to be provided for. By the wisdom of one of the greatest Presidents we ever had, Roosevelt, it’s common knowledge the WPA, a relief program, was established, for, as Roosevelt, said, it was necessary to protect the skills of the American people. With that point of view, it was soon found that the first people who were starving at that time, of course, were the artists and the people in the arts. So quickly, we were all put to work. The best people came to Washington at that time. Roosevelt was a kind of a magnet that attracted the best minds, which, of course, I cannot say for Washington in postwar period, although I think that Kennedy was that kind of a person, too. He could, if he had lived, probably done a little bit more for the spiritual and cultural life of our people. The wonderful thing about that period, Joe to me-was the human quality, the humanist attitude that we had, and I think it was very definitely the result of discovering that the artist was not apart from the people. First of all, we were all in the same boat. We all had to go thru a relief program. We all had to be investigated. In order that the investigator would come to your house, open the icebox and make sure there was nothing inside. Then you were all right.”

- “ As a matter of fact, I think the lesson of our period of the WPA art program and the Section of Fine Arts (referred by Kennedy above-ed note), which I would like to talk to you about later, is something that I talk time and time again everywhere I go. I spoke of it in England and Sweden and France, I spoke of it in Moscow, and Budapest, and Berlin. I feel it is something we should be very proud of, and certainly it is a pattern to remember I would like to see our government returning to this responsibility. You see, I don t go along with all this business of states’ rights and all this. I think that the Federal government today must represent the needs and wishes of the people more and not less, and I believe it is important on every level, municipal, state and federal to establish a vast cultural art program, because, Joe, our profit system is not capable, as I said to cope with it. The artist is the least needed person in our society because no big business can exploit him and make money.”

- “ And I recall at that time the excitement of knowing that while we were here working in New York and doing some pretty damned good stuff, there was a swell group of artists in Chicago and in St. Louis and in San Francisco and in Los Angeles, and every month or two a new work would come up which would challenge everybody, would excite everybody. I remember when I first met Philip Guston, who had just arrived from Los Angeles. We did not know his work, but when I saw Phil’s photographs, especially the mural he did with Kadish for a worker’s school in Los Angeles, I was excited. Every time you see good work something happens to you; you are on a spot.”

- “Bobby Dylan, who lives here in Woodstock, can make a record and it may sell probably a million copies. Well, this is great for Dylan but it’s even greater for the American people. They can have his songs in their homes. But the important thing is it’s only possible because the big manufacturers can make great profit out of their original investment. This does not apply to painting and sculpture; it does not apply to graphic arts; it does not apply to a dance; it does not apply to the majority of composers; it certainly does not apply to poets. Therefore in order that the artist can serve the cultural needs of the people, and I like to use this sentence, I like to use that kind of phrase, I believe it is necessary and essential not to lose the great talent and that is why I say it is necessary for a government program. And I am not worried about waste because let’s remember that, while we have the great wealth of the Renaissance in some of our museums and throughout the world, remember that for every great name we have today there must have been hundreds of other artists who were working, probably not with the same kind of talent, but helped to lift the whole school to a higher level of performance. I’m not worried about the reactionaries who say that the WPA was boondoggling and there were some bad artists on the project. We need everyone who commits himself to the position of being an artist and give him a chance and make sure that we don’t waste a single possible talent, Who in official circles could have told whether Van Gogh was an artist or not at the time when he first started painting.”

- “But l remember in the early period of the Project having lunch one day with Bruce and Rowan who were administrators of the Section of Fine Arts in Washington and they asked me, and I was rather flattered, who the artists I thought at that particular time should have been considered for commissions. Well I said- “Ben Shahn. “”Oh, no,” they said, “No, he’s too modern!” But the important thing is that Ben Shahn did enter competition and won the Washington Social Security Building, did a very distinguished mural Every time this happened it did, of course, raise the level of the performers of the Section I, myself, as you know, competed for the San Francisco Post Office. This was a national competition with 81 artists competing. I was declared the winner, the jury consisted of the previous winners of the previous jobs, Arnold Blanch, Victor Arnautoff, and so on. And of course, I spent two and a half years of the happiest part of my life working on that great Federal program, Section of Fine Arts. It is there for everyone to see, and this is the way mural painting should function.”

ENDURING LEGACY OF THE ARTS

In American Made: When FDR Put The Nation To Work, author Nick Taylor records that one enduring aspect of the WPA was its support for artists and the arts and especially murals that can still be seen in post offices and public buildings.

The WPA provided federal support for the arts that created jobs for artists and a short period of artistic creativity. Hopkins had argued that unemployed painters, writers, actors, and musicians were just as qualified for employment support as any other worker:

- The Federal Arts Project employed 5,000 mural, easel artists, print makers, sculptures, poster artists, and art teachers. Conservative press and politicians criticized this as a giant waste of public money. However, one example is the enduring presence of murals in post offices and other public buildings. This is a tribute to creativity and a celebration of U.S. history by its diverse contributors.[29]

- Another aspect of the Federal Art Project was the deployment of researchers, artists, and photographers who worked at unearthing art and artifacts showing how Americans lived from the 18thcentury onwards. [30]

- The Federal Writers Project created travel guides of states in the United States that not only provided information about tourism but also about state and local history. Some guides have been re-published and provide an historical document about what life was like in various states during the 1930s.[31]

Taylor summarizes these accomplishments as follows:

“The accomplishments of the WPA came to be measured in statistics: 650,000 miles of roads, 78,000 bridges, 125,000 civilian and military buildings, 800 airports built, improved or enlarged, 700 miles of airport runways. It served almost 900 million hot lunches to school children and operated 1,500 nursery schools. It presented 225,000 concerts to audiences totaling 150 million, performed plays, vaudeville acts, puppet shows, and circuses before 30 million people, and produced almost 475,000 works of art and at least 276 full-length books and 701 pamphlets. Such numbers convey almost no impact by themselves. They are silent on the transformation of the infrastructure that occurred, the modernizing of the country, the malnutrition defeated and educational prospects gained, the new horizons opened.’[32]

FOOTNOTES

[1] Quoted by Robert Heilbroner and Aaron Singer, THE ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA: 1600 TO THE PRESENT (1994), p.349

[2] Ibid.

[3] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/1934-the-art-of-the-new-deal-132242698/

[4] https://www.newdealartregistry.org/Home.html

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/arts/new-deal-arts-coronavirus.html?searchResultPosition=1

[6] Roger G. Kennedy, When Art Worked: The New Deal, Art, and Democracy (2009), p.25

[7] Kennedy, jacket cover

[8] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dorothea-Lange

[9] https://www.politico.com/story/2017/05/18/tennessee-valley-authority-created-may-18-1933-238325

[10]https://www.google.com/search?q=tennessee+valley+authority&safe=off&sxsrf=ALeKk00dnNPViM6ZU257qYN9E-Qq36YTRA:1587837816492&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjI94zolITpAhVaPn0KHW4DBmoQ_AUoAnoECCAQBA&biw=844&bih=401#imgrc=WAcTZ3xKW5FtuM

[11] Kennedy, pp 24-25

[12] https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/NRPB/NRPBreport.html

[13] Kennedy, pp 90-91

[14] https://www.tva.com/about-tva/our-history

[15] Kennedy, jacket cover

[16] http://www.sfmuralarts.com/ Please see the murals here: http://www.sfmuralarts.com/find/1.html and : http://www.sfmuralarts.com/find/2.html

[17] https://artmuseum.arizona.edu/artwrite/anton-refregier

[18] http://www.sfmuralarts.com/mural/641.html

[19] Richard Dillion, Thomas Moulin, Don DeNevi, High Steel: Building the Bridges Across San Francisco Bay (1978), p.1

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Gate_Bridge#/media/File:Golden-Gate-Bridge.svg: By Roulex 45 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4216116

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Gate_Bridge

[22] http://www.sfmuralarts.com/mural/640.html

[23] https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt667nd21p/?brand=oac4

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richmond_Shipyards

[25]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richmond_Shipyards#/media/File:Wendy_Welder_Richmond_Shipyards.jpg and – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID fsa.8b08491.

[26] Vallejo, California interview with author

[27] http://www.sfmuralarts.com/mural/639.html

[28] https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-anton-refregier-12689#transcript

[29] Nick Taylor, American-Made: When FDR Put The Nation To Work ( 2008) p.270

[30] Taylor, p.278

[31] Taylor, pp 291-292

[32] Taylor, pp 523-524